Overview

A Dutch HR manager is working for an international company headquartered in the Netherlands, specializing in tubular running services. The company operates under the Anglo-Saxon model, with the Dutch branch mainly responsible for conducting business with European countries, as well as Turkey. The Dutch HR manager operates in an international environment with people from various (cultural) backgrounds and often has to interact with partners, clients and colleagues from abroad both remotely and on-site. The working languages at the company are Dutch and English. Naturally, language is not only about learning new vocabulary and grammar, but also about cultural competence: knowing what to say and how, when, where and why to say it (Hofstede, 2002).

The HR manager experiences cultural differences with his international colleagues in his work life on a daily basis. Reactions and body language vary, as does their interpretation by all of the involved parties, with an abundance of different outward (tip of the iceberg model) expressions (Weaver, 2013). The HR manager would describe the work culture of the company as primarily Dutch, intermingled with influences from other international cultures. The HR manager did not find it inhibitive to answer the interview questions and noted that the company does not currently utilize interpreters, but recalled a situation in which it would have been beneficial to do so.

The HR manager was involved in discussions with partners and clients from England where mutual understanding towards one another was not satisfactory, due to the different respective ways of approaching matters (cultural differences). Both the verbal and non-verbal communication was misinterpreted by both parties more often than not, which lead to matters getting out of hand (Weaver, 2013) as unnecessary discussion over matters of little importance could grow into full-blown misunderstandings, negatively impacting everyone involved as a result of the lack of interpretation.

This highlights a certain lack of intercultural competence, as it is best practice to not assume you understand any non-verbal signals or behaviour unless you are familiar with the culture (Hofstede, 2002; Weaver, 2013). Awareness of one’s own non-verbal communication patterns, as well as not taking a stranger’s non-verbal behavior personally, are key to ensuring that matters unfold smoothly (Hofstede, 2002).

The company has policies against the manifestation of prohibitive and inhibitive issues. An example of this is a strict set of rules to prevent racism and discrimination within the workplace, which highlights that it is both prohibitive and inhibitive to propagate these negativities within the company.

Outcome

Power distance index (PDI) / Hierarchy Acceptance

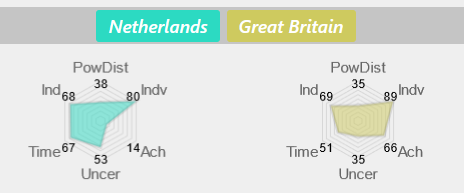

Both the Netherlands and England score alike on the dimension of Power Distance (38 and 35 respectively), evidencing Small Power Distance Orientation (Hofstede, 2002). However, their communication styles differ greatly, as for all of the ‘Dutch directness’ (low context), there is ‘English elusiveness’ (indirectness, high context) to match. The Dutch value of direct communication (bottom of the iceberg model) is not reciprocated. This has on numerous occasions resulted in tensions within the company, as the HR manager felt he practically had to tip-toe around certain people, just to achieve a certain objective. The company is indirectly aware of this happening within the workplace.

When things are not properly interpreted during the meeting and the situation gets out of hand, the meeting is adjourned and postponed until the two parties are ready to resume it. Often, the rest of the business is usually handled over mail. More often than not, it turns out in the end that both parties ultimately meant the same thing but misinterpreted one another.

There are, however, also matters that are scarcely discussed, which the HR manager referred to as ‘lost in translation’, attributing it to the clashes in communication styles, since it is not always clear what the English mean or feel due to their indirectness, clashing with the Dutch ways.

Individualism vs. collectivism (IDV) / Identity

The Netherlands and England both score practically the same (68 and 69 respectively) on the dimension of Individualism. Both countries can misperceive culture-based behavior of foreigners as dishonest or corrupt as a result, depending on the circumstances (Hofstede, 2002). The company’s credo is to do everything together, but in practice those at the company will easily come to see that everyone is for themselves. Even though the company encourages collectivism, the people within the company primarily opt for individualism, unwilling to adjust to the internal company culture, lacking the shared values of collectivism.

Uncertainty avoidance index (UAI)

The Netherlands scores quite higher (53) on Uncertainty Avoidance than England (35), thus exhibiting a slight preference for avoiding uncertainty, compared to the UK, who is more willing to take risks and plunge themselves into the unknown, expressed by the British as ‘muddling through’ (Hofstede, 2002). The Dutch may perceive the British as unprincipled or amoral, while the English may perceive them as rigid and paranoid (Hofstede, 2002).

The HR manager noted that a guiding principle within the company is to always strive to resolve matters immediately and as soon as possible, in order to keep things orderly and on track. Additionally, it is both inhibitive and prohibitive to share information about the company’s inner workings, as evidenced by rules and policies to prevent information about the company’s equipment from leaking out into the public (high confidentiality, NDA’s, etc.). This illustrates the company’s Uncertainty Avoidance.

Masculinity vs. femininity (MAS) / Achievement

There is an overwhelming difference here, with England scoring 66 on the value of Masculinity, compared to the significantly lower 14 of the Netherlands. This means that achievement is more important for the English, compared to the Dutch who place greater value on quality of life.

As such, the English may misperceive Dutch culture-based behavior as weak, from the perspective of achievement (Hofstede, 2002). They will focus on the results and earnings, without placing a focus on more empathetic aspects (Hofstede, 2002). Meanwhile, the feminine Netherlands may misperceive British culture-based behavior as aggressive and braggart.

Long-term orientation vs. short-term orientation (LTO):

The Netherlands scores higher (67) on Time Orientation than England (51), which means that it has a pragmatic nature, compared to England, whose preference cannot be determined due to the intermediate score of 51 (Hofstede, 2002).

In general, the gas & oil industry has a short-term vision because they are forced by governments to do something in the short term. However, the company is developing a long-term orientation as it undergoes a transition phase, which has to do with the current developments in the oil & gas industry. The HR manager’s company wishes to differentiate itself by looking more at the future and developments regarding CO2 emissions, striving to have a better impact on the people, society and world.

Possible Solutions / Best Practice

The best practice approach to solving the issue is for the company to start enlisting interpreters for international meetings, while investing in additional training on intercultural communication for its employees. Extra attention must be paid to meetings and communication with the English to ensure that everyone is on the same wavelength. One of the key methods to break down a language barrier is to find someone who can speak the language as an interpreter and ask for clarification when you are not sure what someone says (Hofstede, 2002).

The company is also working on setting up an international team collaboration training programme in which employees from all over the world will be able to train working together on specific projects, in the hopes that this will add a further boost to teamwork between different cultures.

The HR manager recognizes the importance of adjusting to the way other people may talk in their culture and not taking anything personally. After all, the core of intercultural awareness is learning to separate observation from interpretation (Hofstede, 2002). Postpone interpretation until you know enough about the other culture (Weaver, 2013).

As the intercultural communications skills and awareness are expected to grow following the training, so will the quality of intercultural communication between international partners such as the Netherlands and England, hopefully to the point where additional interpreters will no longer be needed afterwards.

Student Author

Tymoteusz Filipczuk (LinkedIn)

Amsterdam School of International Business, 2nd year International Business, The Netherlands

Block 4, Semester 2 2020/2021