Overview

This international organisation provides leadership coaching and consulting services, with a mission to promote sustainable growth and effective team dynamics. Operating across various regions, including Europe, Africa, and America, the organisation tailors its approach to address cultural and organizational challenges. They face recurring issues such as skepticism toward women and non-European consultants, communication differences, and language barriers. These are addressed through adaptive frameworks and core values like transparency, inclusivity, and respect. Their long-term strategy focuses on fostering trust and creating culturally sensitive environments that prioritise sustainable development.

To address cultural differences, the organsation implements inclusive practices, such as serving only vegetarian meals during meetings, to accommodate diverse cultural and religious practices within their workforce. By understanding Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, the organisation tailors solutions to different cultural contexts, facilitating collaboration and inclusivity across global teams.

Hofstede Dimensions

The organisation is dedicated to consulting and leadership coaching for entrepreneurs and scale-ups, operates internationally, dealing with diverse cultural environments. In regions such as South Africa, the United States of America, the Netherlands, and Turkey, the organisation can navigate these cultural differences using Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. The company’s core values of respect, transparency, and adaptability shape its approach to overcoming challenges in these varied cultural contexts (Hofstede Insights, n.d.).

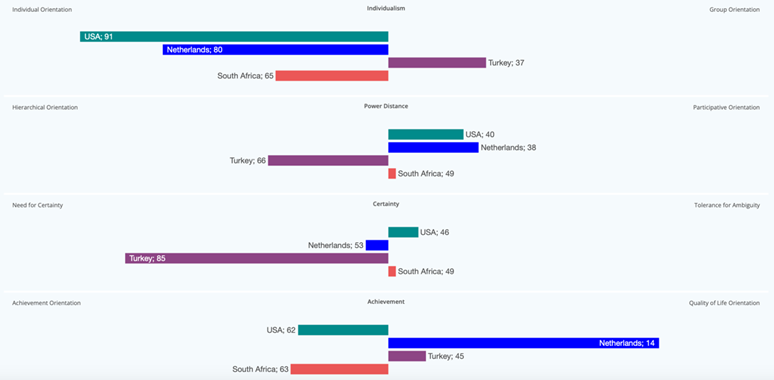

Power Distance Index (PDI): Navigating Hierarchy and Authority

The Power Distance Index (PDI) measures societal acceptance of power inequality. Lower PDI cultures like South Africa (PDI = 49) and the United States (PDI = 40) value egalitarianism, aligning with the organisation’s collaborative approach. In contrast, Turkey (PDI = 66) accepts more hierarchical structures, requiring the organisation to adopt a more structured leadership style while maintaining transparency. Clear role expectations and mentorship can balance these preferences with the organisation’s values (Hofstede Insights, n.d.).

Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV): Adapting to Group vs. Individual Focus

The IDV dimension reflects whether societies prioritise individual or group goals. South Africa (IDV = 65) and the United States (IDV = 91) are highly individualistic, aligning well with leadership coaching focused on personal achievement. In more collectivist cultures like Turkey (IDV = 37), success is tied to group goals. The organisation should frame individual growth as benefiting the team to respect collectivist values while encouraging personal development (Hofstede Insights, n.d.).

Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI): Managing Risk and Ambiguity

The UAI measures tolerance for uncertainty. The United States (UAI = 46) and the Netherlands (UAI = 53) demonstrate low UAI, showing openness to innovation and flexible approaches. In contrast, Turkey (UAI = 85) and South Africa (UAI = 49) prefer clear guidelines and structured processes. The organisation should provide well-defined frameworks and short-term goals in high-UAI contexts, ensuring trust while encouraging long-term adaptability (Hofstede Insights, n.d.).

Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS): Addressing Gender Norms and Bias

This dimension distinguishes competitive, masculine cultures from cooperative, feminine ones. The United States (MAS = 62) and South Africa (MAS = 63) lean towards masculinity, valuing competition and assertiveness. Conversely, the Netherlands (MAS = 14) prioritises equality and collaboration. Gender bias is a challenge, especially in masculine cultures, where women face barriers in leadership roles. Mentorship programmes and leadership training addressing gender bias can help foster inclusivity. For instance, encouraging women in traditionally male-dominated roles in the United States and South Africa can promote equitable opportunities (Hofstede Insights, n.d.).

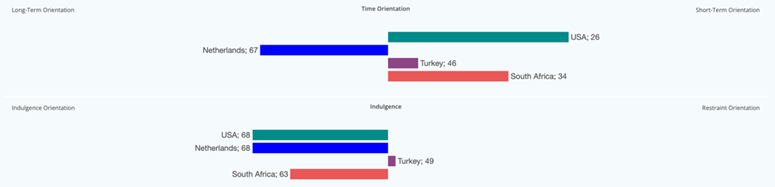

Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation (LTO): Aligning Strategic Goals with Cultural Values

The LTO dimension reflects the balance between long-term goals and short-term outcomes. The United States (LTO = 26) and South Africa (LTO = 34) are short-term oriented, focusing on immediate results. In these regions, achieving quick wins can sustain motivation while advocating for long-term sustainability. In Turkey (LTO = 46) and the Netherlands (LTO = 67), which are more long-term oriented, coaching should emphasise strategic vision and resilience to align with cultural preferences (Hofstede Insights, n.d.).

Communication Challenges: Navigating Cross-Cultural Differences

Cultural differences in communication styles present challenges. The Dutch preference for directness may clash with Turkey’s indirect approach, where bluntness could be seen as rudeness. Adapting communication styles, such as using a diplomatic tone in Turkey, can foster mutual understanding. Addressing gender and racial biases is also critical, especially in regions where consultants from underrepresented groups face challenges. Mentorship and diverse role models can empower leaders and break down barriers (Hofstede Insights, n.d.).

Conclusion

The organisation’s leadership coaching must adapt to diverse cultural dimensions to remain effective globally. By addressing cultural variations in power dynamics, individualism, uncertainty tolerance, and communication, the organisation can uphold its values of inclusivity, transparency, and respect while fostering impactful leadership across markets (Hofstede Insights, n.d.).

Outcome

The application of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions has empowered the organisation to navigate the cultural nuances and challenges inherent in international leadership and consulting. By aligning its leadership strategies with Hofstede’s framework, the organisation has successfully created a culturally inclusive environment, acknowledging the prohibitive and inhibitive elements of diverse cultural norms. This approach allows the organisation to respect and adapt to cultural expectations while upholding its core values of transparency, respect, and adaptability (Hofstede, 2001; House et al., 2004). In doing so, the organisation has been able to foster collaboration across its diverse team of entrepreneurs, scale-ups, and consultants worldwide.

Key outcomes include:

- Cross-Cultural Adaptability:

Hofstede’s power distance dimension has allowed the organisation to adjust its leadership models in a way that aligns with both social norms and laws governing hierarchies in different cultures. For example, in Turkey, where power distance is relatively high (PDI score of 66), hierarchical structures are ingrained as part of the societal mores (Hofstede Insights, 2024). In contrast, in the Netherlands (PDI score of 38) and the United States (PDI score of 40), which have lower power distance, a more egalitarian leadership style is considered the folkway (Hofstede, 2001). The ability to accommodate these cultural differences in leadership structures ensures that the organisation’s strategies are not only culturally appropriate but also effective in fostering collaboration.

- Promoting Gender Equality in Leadership:

The organisation has developed targeted programmes to address gender bias, which is often seen as taboo or a social norm in certain contexts, particularly in higher-ranking leadership roles. In countries like the USA (MAS score of 62) and South Africa (MAS score of 51), where gender biases might still manifest in business settings, the organisation has introduced narratives that focus on female empowerment, ensuring women have the opportunity to thrive in leadership positions (Hofstede Insights, 2024). These narratives, grounded in Hofstede’s masculinity versus femininity dimension, are designed to challenge inhibitive norms and offer an equitable platform for women to develop leadership skills, contributing to more balanced organisational structures.

- Improving Communication Across Cultures:

The organisation has used Hofstede’s uncertainty avoidance dimension to understand the cultural differences that affect communication between regions. The Dutch directness, which is considered a folkway in the Netherlands, can be seen as inhibitive to effective communication in more indirect cultures like Turkey (Hofstede Insights, 2024). In Turkey, with its high score for uncertainty avoidance (85), communication tends to be more formal and less direct. The organisation has developed culturally relevant communication strategies that address these differences by training employees to adapt their communication styles, thus avoiding potential misunderstandings. This ability to navigate cultural communication norms ensures that the organisation’s message is clear and inclusive, regardless of the cultural context.

- Balancing Short-Term and Long-Term Focus:

The organisation has also integrated Hofstede’s long-term orientation dimension into its strategic planning to navigate the differing narratives of time and success across cultures. In cultures like the Netherlands, which has a strong long-term orientation (LTO score of 67), decisions are made with an eye on future sustainability, reflecting societal values that prioritise foresight (Hofstede Insights, 2024). However, in countries with a stronger short-term orientation like the USA (LTO score of 26) and South Africa (LTO score of 34), the organisation remains flexible, adapting to the more immediate business demands reflective of those cultural norms. By balancing both perspectives, the organisation avoids falling into rigid prohibitive mindsets and ensures long-term success without disregarding the immediate needs of the business.

The organisation’s ability to apply Hofstede’s cultural dimensions demonstrates its commitment to culturally inclusive leadership practices. By embracing the diverse folkways, mores, and taboos inherent in each culture, the organisation has effectively navigated the challenges of international leadership and consulting. Through its adaptable and culturally sensitive approach, the organisation has addressed issues like gender bias and communication difficulties, ensuring the continued success of its operations in a globalised business environment (Hofstede, 2001; House et al., 2004).

Possible solutions

To address the cultural challenges highlighted across various Hofstede dimensions, the organisation can implement several strategies to ensure its leadership coaching and consulting services remain effective and adaptable:

Cultural Awareness and Sensitivity Training:

Developing training programmes based on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions equips consultants to navigate diverse environments. For instance, understanding power-distance dynamics in hierarchical cultures like Turkey allows for respectful and effective communication. Research shows that such training improves cross-cultural collaboration and reduces misunderstandings (Hofstede, 2011). However, one challenge in implementing such programmes lies in ensuring that the training is not overly prescriptive or stereotypical. If the training is based solely on broad cultural dimensions without considering individual or organisational variations, it may reinforce biases rather than overcome them. Therefore, it is essential to tailor the training to the specific context of the organisation, continually updating content to reflect evolving cultural dynamics.

Flexible Communication Frameworks:

Intercultural communication training is essential to bridge communication gaps. For example, balancing Dutch directness with Turkish relational approaches can prevent miscommunication. Ting-Toomey and Chung (2012) emphasise that culturally adaptive communication fosters trust and minimises friction in global teams. One challenge with implementing flexible communication frameworks, however, is the difficulty in getting individuals to break long-standing cultural habits. People may resist changing how they communicate, particularly if they feel that their cultural identity is being compromised. Therefore, it is important to create an environment that fosters openness to intercultural learning, where employees can experiment with new communication styles without fear of failure or judgment.

Structured Coaching for High Uncertainty-Avoidance Cultures:

In regions with high uncertainty avoidance, such as Turkey, structured workflows and clear roadmaps reduce ambiguity and build trust. Hofstede Insights (n.d.) highlights that providing clarity and predictability is critical in such cultures to ensure smooth collaboration. However, one limitation of this strategy is that excessive structure can stifle creativity and adaptability, which are also valuable in today’s rapidly changing business environments. Balancing the need for structure with the flexibility to innovate is a delicate challenge that organisations must navigate. This can be managed by periodically reviewing the effectiveness of coaching approaches and adjusting them based on feedback from participants.

Promoting Gender and Racial Inclusivity:

Mentorship programmes for women and underrepresented groups are essential, especially in masculine cultures like the United States and South Africa. Catalyst (2020) reports that mentorship programmes significantly improve representation and performance outcomes for women in leadership roles. These programmes should also challenge biases through role models and inclusive policies. A potential challenge, however, is the risk of tokenism, where initiatives may be implemented to appear inclusive without making meaningful structural changes. Therefore, mentorship should be part of a broader diversity strategy that includes policy changes, performance metrics, and a commitment to long-term cultural change.

Tailored Leadership Development Programmes:

Leadership coaching must align with cultural preferences. In short-term oriented cultures like South Africa and the United States, focusing on immediate, tangible successes motivates teams while preparing them for long-term goals. Conversely, in long-term oriented cultures like the Netherlands, emphasising resilience and strategic vision resonates more strongly (Hofstede Insights, n.d.). A challenge to this approach lies in the potential for misalignment between leadership development programmes and organisational objectives. For instance, in multinational organisations, different teams may have divergent priorities, making it difficult to create a uniform leadership development model. It is essential to continuously assess how well leadership development initiatives align with both cultural preferences and organisational goals.

Enhanced Use of Technology for Multilingual Support:

Leveraging translation tools and multilingual communication platforms ensures accessibility and inclusivity. Such tools reduce language barriers and foster smoother interactions across diverse teams (Peterson, 2018). However, technology alone cannot replace the nuance of human communication. Automated translation tools can often result in errors or loss of context, which could lead to misunderstandings. Therefore, while technology is a valuable tool for inclusivity, organisations must combine it with human oversight, ensuring that culturally sensitive language and tone are preserved.

Conflict Resolution Mechanisms:

Structured protocols tailored to cultural preferences help manage misunderstandings effectively. For example, in collectivist cultures like Turkey, indirect communication and diplomacy are vital to resolving conflicts constructively (Ting-Toomey & Chung, 2012). While this approach can be effective in certain contexts, it may be met with resistance in more individualistic cultures where direct confrontation is viewed as a necessary component of problem-solving. One challenge, therefore, is finding a balance between indirect and direct communication styles. Additionally, conflict resolution methods that prioritise harmony can sometimes suppress necessary debates or lead to unresolved issues, thus hindering progress.

Dietary and Cultural Accommodation Policies:

Offering vegetarian or vegan meals during events respects dietary restrictions and cultural prohibitions while promoting sustainability. This approach aligns with UNESCO’s (2021) recommendations on fostering inclusion through cultural sensitivity. However, the implementation of such policies may face resistance, particularly in environments where dietary habits are strongly tied to cultural or regional identity. Additionally, the logistics of providing culturally appropriate meals for diverse groups can be complex and costly. Thus, it is important to balance inclusivity with practicality, ensuring that the needs of all participants are met without compromising the efficiency of the event.

Feedback Loops for Continuous Improvement:

Establishing feedback mechanisms allows strategies to evolve dynamically. Reiche, Harzing, and Tenzer (2016) highlight that regular feedback fosters cultural adaptation and enhances organisational performance in multinational teams. However, feedback can be influenced by cultural norms regarding authority and hierarchy. In cultures with high power distance, employees may be hesitant to provide honest feedback to senior leaders. To overcome this challenge, feedback systems should be designed to allow anonymity and foster a safe space for constructive criticism. Additionally, feedback should be taken seriously, with visible actions taken to address concerns raised.

In conclusion, the implementation of culturally sensitive leadership coaching and consulting strategies, guided by Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, presents a comprehensive approach for enhancing cross-cultural collaboration and inclusivity. By focusing on critical areas such as communication, structured coaching, gender and racial inclusivity, and tailored leadership development, organisations can foster an environment conducive to the growth of diverse teams. These strategies, however, must be continually reassessed and adapted to meet the unique needs of different cultures and organisations. Success hinges on the flexibility and responsiveness of these approaches, ensuring they are dynamic and evolve with the changing demands of global business contexts. Regular feedback and an ongoing commitment to cultural awareness are integral in maintaining the effectiveness of these strategies, ensuring that leadership initiatives contribute to both individual and organisational success.

Authors

- Julia Louise Impey

International Business, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences

Block 2, Semester 1, 2025 - Gerda Kalinkaite

International Business, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences

Block 2, Semester 1, 2025 - Nina Geestman

Student: International Business, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences

Block 2, Semester 1, 2025 - Sana Faraz

Student: International Business, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences

Block 2, Semester 1, 2025

References:

- Catalyst. (2020). Mentorship and sponsorship for women in leadership. Catalyst.

- Catalyst. (2020). Why diversity and inclusion matter: Quick Take. https://www.catalyst.org

- Hofstede Insights. (2024). Country comparison dashboard. https://cultureinworkplace.com/country-comparison-dashboard/?ode-country-selected=US,TR,ZA,NL

- Hofstede Insights. (n.d.). Country comparison tool. Hofstede Insights. https://cultureinworkplace.com/country-comparison-dashboard/?ode-country-selected=US,TR,ZA,NL

- Hofstede Insights. (n.d.). Country comparison. https://www.hofstede-insights.com

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage Publications.

- Peterson, B. (2018). Cultural intelligence: A guide to working with people from other cultures. Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Reiche, B. S., Harzing, A. W., & Tenzer, H. (2016). The cultural context of leadership and teams. The Journal of International Business Studies, 47(3), 307–332.

- Reiche, S. B., Harzing, A.-W., & Tenzer, H. (2016). Managing international teams. In S. B. Reiche, A.-W. Harzing, & H. Tenzer (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of international organizational behavior (pp. 33–54). SAGE Publications.

- Ting-Toomey, S., & Chung, L. C. (2012). Understanding intercultural communication (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- UNESCO. (2021). Fostering inclusion and sustainability through cultural practices. https://www.unesco.org

- UNESCO. (2021). Inclusion in education: All means all. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.